Homeland Security funding bill falters again in Senate as Republicans

warn of Iran risk

[March 06, 2026]

By KEVIN FREKING

WASHINGTON (AP) — Republicans invoked the war in Iran and the prospect

of retaliatory terrorist attacks as they made another unsuccessful

effort Thursday to pass a bill funding the Department of Homeland

Security.

Democrats are insisting on changes to immigration enforcement operations

as part of the measure and blocked it from advancing. The procedural

vote was 51-45, falling well short of the 60 that Republicans needed to

proceed with the measure.

The House also took up the bill on Thursday, passing it 221-209, but in

the end, a bipartisan compromise will have to be reached to end a DHS

shutdown that began Feb. 14.

The funding bill first passed the House back in January, but it has gone

nowhere in the Senate as Democrats seek new restraints on immigration

enforcement tactics following the killing of ICU nurse Alex Pretti by

Border Patrol officers in Minneapolis.

Republicans have called on Democrats to reconsider their vote in the

wake of the conflict in Iran.

Sen. John Barrasso, the No. 2 Republican in the Senate, said Democrats

would bear responsibility for the next cyberattack that is missed or the

next “lone wolf terrorist” who attacks in the U.S.

“Blood will be on their hands,” Barrasso said on the Senate floor.

It did not appear the GOP's strategy had changed the position of

Democratic lawmakers, though. They said they are prepared to fund most

of the agencies in the department, just not Immigration and Customs

Enforcement or Customs and Border Protection.

“It's the same lousy, rotten bill that does not put any guardrails or

constraints on ICE or CBP after federal agents shot American citizens in

the street,” said Rep. Jim McGovern, D-Mass.

Moments before the vote, senators were getting word that President

Donald Trump had just fired DHS Secretary Kristi Noem. The news did not

change Democrats' resolve to force operational changes within the

department through the spending bill.

“Good riddance," said Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer. “But the

problems at ICE transcend any one individual.”

Workers are beginning to miss part of their paychecks

Following the longest federal shutdown in the country’s history last

year, Congress has completed work on 11 of this year’s 12 appropriations

bills. Only the bill for Homeland Security remains outstanding.

Republicans said the timing couldn't be worse for a Homeland Security

shutdown. While a large majority of the department's employees are

considered essential and continue to work, many will not receive a full

paycheck this week.

“Like Democrats’ first shutdown a few months ago, this shutdown is

causing a lot of financial stress, uncertainty, and pain for hardworking

Americans,” Senate Majority Leader John Thune said. “It’s also making it

harder for those working to keep America safe.”

Republicans said the prospect of an increase in unscheduled absences by

the Transportation Security Administration's agents could lead to longer

wait times at the nation's airports. Meanwhile, the Cybersecurity and

Infrastructure Security Agency has canceled various assessments to

determine vulnerabilities to critical infrastructure. And training for

first responders conducted through the Federal Emergency Management

Agency was canceled.

[to top of second column]

|

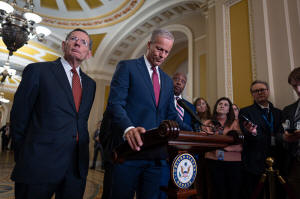

Senate Majority Leader John Thune, R-S.D., center, joined at left by

Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyo., the GOP whip, speaks to reporters at the

Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott

Applewhite)

Democrats are seeking several changes at the department that include

prohibiting ICE enforcement operations at sensitive locations like

schools and churches, allowing independent investigations into

alleged wrongdoing, requiring warrants to be signed by judges before

federal agents can forcibly enter private homes or other nonpublic

spaces without consent, and requiring agents to wear identification

and remove their masks.

Republicans note that the bill does include a bipartisan provision

directing more resources for de-escalation training and $20 million

to outfit immigration enforcement agents with body-worn cameras.

Little to show from negotiations

The White House and congressional Democrats don't appear to have

made significant progress in recent weeks in resolving their

differences after trading offers.

“Look, we're still far apart, but we're negotiating and exchanging

paper back and forth,” Schumer said.

The size of the divide appeared significant during Thursday's

debate.

Alabama Sen. Katie Britt said that through their actions, Democrats

were “still the party of open borders, they are still the party of

defund the police, now actually more than ever.”

She and other Republicans also cited last weekend's mass shooting in

Austin, Texas, as an example of the dangerous threat environment

that's facing Americans following the attack on Iran.

“We know this couldn't come at a more dangerous time," Britt said.

Sen. Patty Murray, the top Democrat on the Senate Appropriations

Committee, said that Democrats were simply working to make sure

federal immigration officials follow the same standards as other law

enforcement officers. She offered an alternative bill to fund all

the agencies within Homeland Security, except for ICE, Customs and

Border Protection, and the office of the secretary, but it was

rejected.

“We are not asking for the moon," Murray said. "... There is nothing

extreme about ICE and Border Patrol following the same standards as

everyone else when it comes to use of force or needing a warrant

before smashing in someone's window and dragging them away.”

___

Associated Press writer Mary Clare Jalonick contributed to this

report.

All contents © copyright 2026 Associated Press. All rights reserved |